Subverting algorithmic policies of sonic control in Nicolas Collins’s Broken Light (1992)

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- On Broken Light

- On algorithmic policies of sonic control

- Conclusion

- Funding acknowledgment

- Works cited

Details

This paper will be presented as

- Eamonn Bell, “Subverting algorithmic policies of sonic control in Nicolas Collins’s Broken Light (1992)” at 18th Annual Conference of the Society for Musicology in Ireland, University College Dublin/Virtual. (October 29—31 2020).

- Eamonn Bell, “Subverting algorithmic policies of sonic control in Nicolas Collins’s Broken Light (1992)” at Joint Annual Meeting of the American Musicological Society and the Society for Music Theory (AMS/SMT), Virtual. (November 7–8, 14–15 2020).

Slides

A PDF file with the slides for this presentation are available for download here (27.6 MB). Slides integral to the talk as typewritten are included in the text below.

Video

A video of this presentation as it was delivered at AMS is available for download here (40.3 MB) It can also be accessed on the AMS conference platform or by emailing me at belle2@tcd.ie.

Acknowledgments

Nicholas Brown, Natasha Calder, Nicolas Collins, Rodrigo Costanzo, Cormac Deane, Kyle Devine, Ezra Teboul, Kurt James Werner

Introduction

In this talk, I focus on the second movement of Nicolas Collins Broken Light, a piece for modified Discman and string quartet composed in 1991 and revised in 1992. Sound art historian Caleb Kelly has already overviewed Collins’s musical experiments with CD media in his 2009 survey of sound art and composition that featured “cracked” technical media: both destroyed vinyl records and damaged compact discs.1 More recently, both Greg Hainge and Marie Thompson have separately discussed Collins’s compositions. Both authors are primarily concerned with standard and non-standard ontologies of noise, with Hainge seeking to advance the discourse on digital glitches by attending more carefully to how critics figured the distribution of agency in earlier writing about certain CD-based compositions from the final decades of the twentieth century.2 Precisely how actually existing signal processing techniques should inform ontologies of noise itself is an open and vexed question, however.3 Thompson’s Spinoza-inspired relational ontology of noise might offer a genuine solution. In her monist account, CD-based experimental compositions—including those of Nicolas Collins—show that material–technological agents can also be said to draw the line between signal and noise.4

Setting such questions of ontology to one side, I’d like to take a more pragmatic look at Broken Light and confront how this piece treats the audio CD format in terms native to the analysis of music and of the analysis of signals.5 My discussion of Broken Light is partly indebted to the recent work on “non-discursive” materials of electronic music practices—namely circuits—by You Nakai and Ezra Teboul, whose most recent writing charts viable way forward for a circuit-first history of experimental electronic music grounded in insights from STS.6 I also draw on motifs from the field of media archaeology. In the last 20 years or so, North American and European scholars alike have embraced the sustained and often very hands-on investigation into the operating principles of technical media: phonography, early cinema, early television as well as less automatic but equally mediated objects like grids, lists, and files.7 These investigations are indebted to the anti-hermeneutics of the Germanist-turned-German media theorist Friedrich Kittler, to whose notions about media I’ll make occasional reference.8

In what follows, I will argue that the piece discloses the algorithmic policies of sonic control that characterize consumer digital audio in the final decades of the twentieth century. In short, these algorithmic policies of sonic control autonomously determine what and when data is realized as sound and under what contexts with little oversight on the part of the listener. First, we’ll listen to a short excerpt from Broken Light and see how a circuit-based analysis of its modified Sony Discman D-2 clarifies how the piece was put together. Then, I’ll turn to a more general consideration of features of the digital audio CD format as they are indexed by how Broken Light, and identify the algorithmic policies of sonic control at stake in most CD players. Most generally stated, I set out to better understand the role that histories of musical creation and performance can play in filling in the bigger picture of the compact disc’s cultural moment.

On Broken Light

Nicolas Collins’s Broken Light (1992) is an electroacoustic composition that explores the distinctive skipping sound that CD players make as they fail to read audio data from the medium’s surface. Collins (b. 1954), a one-time student of Alvin Lucier and David Tudor, was appointed as a Professor in the Arts Institute of Chicago since 1999 and is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of an empirical, experimental approach to the use of modified consumer electronics in electroacoustic music and sound art.9 Written for “string quartet and modified Discman”, Broken Light stages an encounter between performers, separated in time and space with the help of technical media. At one pole, the members of the Solider Quartet, who improvise using a semi-open score. At the other, members of the early music group I Musici, who are represented in absentia by their 1984 all-digital recording of Baroque-era concerti grossi, released on CD on the Philips Digital Classics series in 1990 under the title “Christmas Concertos.”10

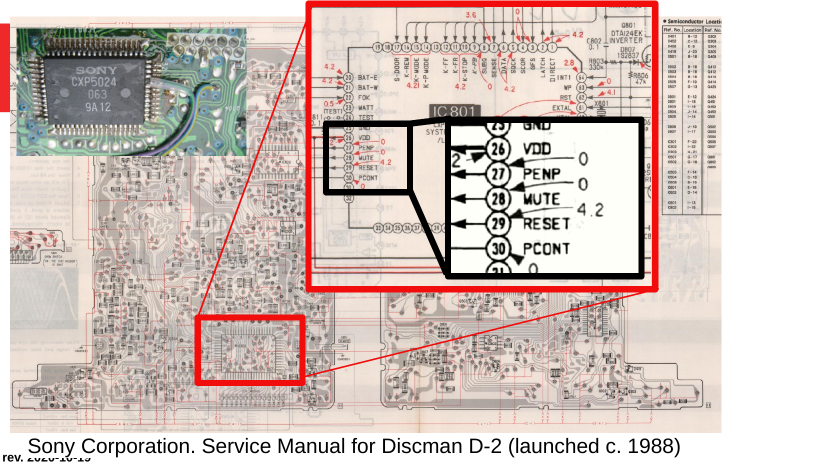

To realize Broken Light, Collins modified—in his words, “hotwired”—the circuits inside a Sony Discman D-2, an early model portable CD player launched circa 1988, some six years after the launch of the format in the Japanese market. Collins claims that while inspecting a schematic diagram for the Discman D-2 in a service manual, he noticed that one of the hundreds of signals emanating from the various chips inside the player was labeled “MUTE.”11 Shown here is the same circuit diagram, and inset is a detail from Collins’s modified player. Knowing that the disc player relied on digital communication between its various parts and curious about its function, Collins explored what would happen if he could inhibit the electronic signal flowing from the MUTE pin on the main playback controller chip (IC 801 on the schematics) to other parts of the Discman circuit board. Collins de-soldered the electrical contact from the board and re-routed the path of the MUTE signal to a switch that he could flip on and off at will. Now, the chip could no longer communicate with muting circuitry elsewhere in the device.

The composer found that the CD player in its “pause” state was no longer silent as a consequence of this modification: instead, the player would diligently repeat the same subsecond fragment of sound over and over again, with minor timing variations. Similarly, when the modified player was made to skip over entire tracks, it emitted quick flurries of sound where once it moved from track to track in digital silence. Collins reasoned—correctly—that blocking the MUTE signal caused his player to emit these sounds because the player’s optical block continuously read data off the disc medium even when the player was supposed to be paused. The high speeds and rotational inertia of the spinning compact disc mean that braking the disc and bringing it to a halt prohibits a quick recovery after push-button pauses. What made the Discman D-2 distinctive (but not unique) was that the paused player continued to read the sequence of pits and lands off the surface of the disc and interpret them as audio. When the MUTE signal is allowed to pass freely, this happens totally silently as the recorded sound sits in limbo. When the MUTE signal is inhibited, however, we become privy to the ordinarily silent inner workings of the compact disc player.

Taking all of this into consideration, Collins wired up his modified player so that one member of the quartet could control the behavior of the player using footswitches that “nudge” (N), and “skip” (S) the Discman’s path forward through each of the three movements of Baroque music that lie behind each of the three movements of Broken Light. The composer explains:

Under the control of the performers, the CD player “scratches” across the disk, isolating and freezing short loops of recorded music. As it slowly steps from one “skipping groove” to the next, the lush contrapuntal texture of the concerto grosso is suspended in harmonic blocks, with the insistent rhythmic feel of the loop superimposed. The performers’ parts, both written and improvised, mesh and clash with the CD, with a respectful nod to Terry Riley’s In C.12

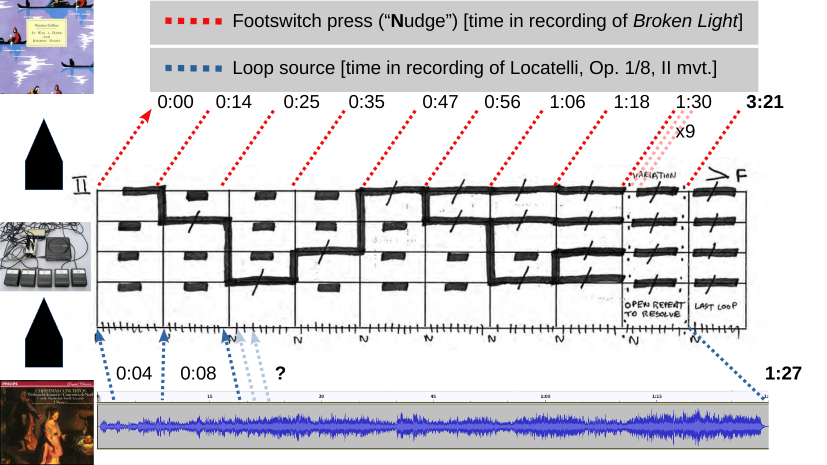

As clarified by a set of accompanying instructions, the score for the second movement excerpted here uses a thick black line to indicate when each instrumentalist is playing. Players aim to match pitch names that they hear represented in the background harmony provided by the looping Baroque recording. As the black line “passes” from instrument to instrument and new part-combinations are explored, musicians initially copy the pitch names played by their predecessors. Every 15 seconds or so, one member of the quartet briefly taps the “N” footswitch to nudge the Discman forward. This results in a change of harmony in the background loops, while the instrumentalists sustain their pitch choices from the previous block. Elegant suspension-like figures emerge from these simple rules; where the score indicates a diagonal line approximately mid-way through each block, players must “resolve” these dissonances to a pitch that they hear represented in the looped material. About 19 foot-taps later, about 3 minutes of performance time has passed. At the same time, we have reached a definitive close in F plundered from the source material: the second movement of Pietro Antonio Locatelli’s Op. 1, No. 8 concerto grosso, a lively fugal movement within a modified sonata da camera form. Let’s listen now to the first minute or so of the second movement of Broken Light.

After a couple of close listenings, I began to think about the function of the modified Discman as effecting a kind of transformation between the source recording track and the recording of the performance. This annotated score adopts this perspective, showing how the footswitch presses, shown in red, are distributed relatively evenly throughout the second movement. A blue dotted line connects each successive “harmonic block” back to its approximate location in the source track. At 1 minute and 30 seconds, the source track is half as long as the final product, giving a coarse sense of how the Discman mediates between the time of the source recording and the unfolding improvisations that accompany them. Looking at the outer movements of Broken Light shows they delineate a conventional fast–slow–fast structure for Collins’s composition as a whole. Therefore, recalling that the source material from Locatelli’s concerto grosso is a faster-than-average fugato movement marked “Vivace” shows that the modified CD player further rewrites time to make source material in a tempo associated with one generically typical position in one multi-movement work fit the generic norms associated with another. Add to this the match between the “expository” structure of first four harmonic blocks in Broken Light and the imitative opening passages of the Locatelli. Furthermore, the typical concerto grosso disposition of performers into concertante soloists and the ripieno sub-ensemble is redoubled in Broken Light, with all the I Musici players relegated to the ripieno function within the larger frame of Broken Light’s electroacoustic consort of Discman and string quartet.

Here the portable compact disc player acts as nothing less than what Wolfgang Ernst would call a “sonic time machine”, drawing disparate spaces and times together through the action of an operative technical medium.13 The optical readout of the digital audio CD not only brings performances long past into tangent with each other but also affords the juxtaposition of artistic conventions internal to music composition that are otherwise distant by hundreds of years. And, in other pieces—including Still Lives (1992), Die Schatten (1996) and English Music (2002)—Collins would continue to explore precisely this generative capacity of modified CD players. Each of these pieces cites or quotes earlier recordings of yet earlier compositions, often earlier by centuries. Most of these performances have themselves in been turn recorded distributed digital, in some cases, on CD. Excitingly, there is yet further scope to glean potentially meaningful data from the media-archaeological record, aided by the signal-processing tools I used in the preparation of the annotated score.14 Close readings of these time-shifting works, all of which exploit the fact that normally-operating CD players rely on the effective passage of “MUTE” messages between the microchips on their surfaces, points to the fact that the high-fidelity digital experience that CD represents is as much about the careful control of silence as it is about the careful control of sound. To the consequences of this fact we now turn.

On algorithmic policies of sonic control

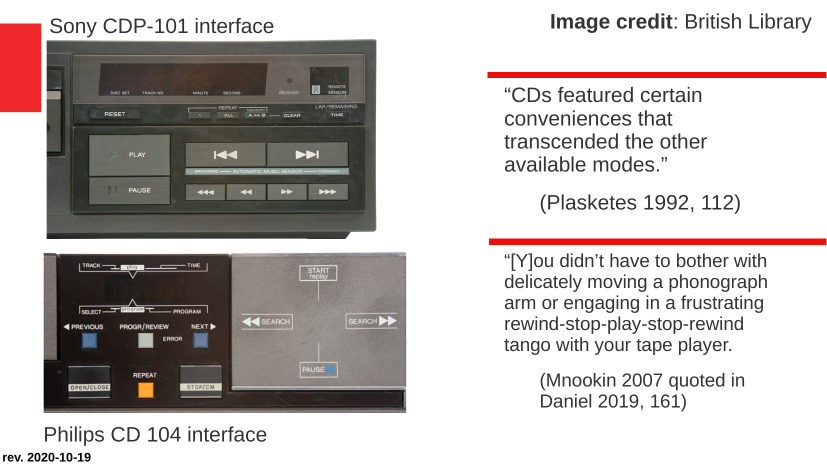

In a perceptive early essay about the CD’s impact on vinyl, George Plasketes noted that “CDs featured certain conveniences that transcended the other available modes.”15 Reflecting with the benefit of hindsight on the reasons for the CD’s success relative to vinyl, journalist Seth Mnookin wrote: “you didn’t have to bother with delicately moving a phonograph arm or engaging in a frustrating rewind-stop-play-stop-rewind tango with your tape player.”16 In early advertising that described these convenient playback and cueing features, manufacturers emphasized the unprecedented control over playback that digitalization seemed to afford.17 For instance, the first Sony-manufactured CD player to make it to market in late 1982 supported an infrared wireless remote control, a feature that most televisions in use at that time did not.18 This magazine advertisement for the Sony CDP-101 that ran in 1983 explained that its remote control “even lets you select tracks without budging from your armchair”, promising the convergence of space and time and all the thrill of remaining fixed to the seat in “seventh row, center.”19

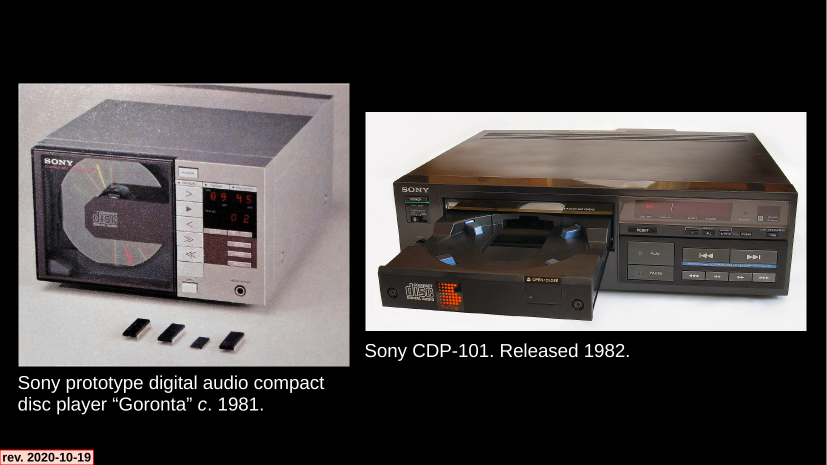

Yet in the years following the launch of the format, some audio customers felt increasingly excluded from understanding the in and outs of the new paradigm for sound reproduction that the CD represented. Marc Perlman has described how some audio consumers responded to their increased abstraction from the processes of sound reproduction with “tweaks”, which were generally directed at the few components of the CD system that remained user-serviceable.20 The difference in the design between the prototype digital audio disc players developed by Sony and the final design of the first commercially available CD player is telling. Sony’s prototype player, nicknamed Goronta, featured a front-loading CD carriage: the spinning CD was proudly displayed in a plane perpendicular to the viewer’s gaze. But by the release of the CDP-101 in late 1982, Sony had developed the familiar automated sliding tray that ingested the disc media deep into the bowels of the unit, leaving it hidden from view. A similar story shapes the evolution of the Philips prototype.21

The significant irony is that the cueing features that manufacturers introduced to compensate for the process of literal enclosure briefly sketched here, were themselves implemented and enclosed within the microscopic silicon chips that made up each player’s microcircuitry. As Broken Light suggests, the manufacturers who implemented the cueing and seeking features of computer-controlled CD players used muting liberally to deal with disc media in motion, suppressing the sounds of the spinning disc infrastructure on which sound reproduction was premised. Each CD player materializes a slightly different slate of what I call policies of sonic control. Its circuits and microcode regulate what and when the data that the medium inscribes is understood as sound and what and when is understood otherwise. The CD system as a whole does so by referring to a schedule of what is considered “good” or valid in a given setup: in other words, a policy.22

These policies of sonic control are algorithmic since they operate more or less autonomously; generally, but not always, without the oversight or control of their users. How they work is determined not only in the design of the player hardware but also in computer code that is written specifically to run on the combination of microcircuits often unique to each player. Proprietary and lightly documented technologies raise the barrier to meaningful control over the player’s behaviors so high as to be unattainable. As a result, these policies are not user-modifiable—at least, not without significant deviation from the intended uses of the player.23 This has much in common with the condition of the early-90s PC user that so exercised Kittler in his essay “Protected Mode”, an important entry in the canon of German media theory because of its explicit treatment of questions of power and control with which Kittler’s writing is not generally concerned.24 In this essay, the German media theorist analyzed changes that had taken place in both the design of the processor architecture in then-modern IBM-compatible PCs and the documentation made available to programmers, to argue that computer users had been increasingly abstracted from the mechanisms of operation of the technology that they owned.25

In the final leg of this paper, I discuss how the enigmatic circuit-based manipulations of the Discman’s muting features in Broken Light index yet another algorithmic policy of sonic control enforced by CD players, one that is well known to audio professionals but has been, to date, little-remarked upon by creative artists and scholars of sound media.26 It is well known that CDs are resistant to dirt, dust, and fingerprints because the CD system uses sophisticated error detection and correction techniques to mitigate the effect of these pollutants on audio playback.27 By strategically adding extra data to the disc that exceeds the digitized audio signal, well-understood mathematical techniques can be used to reconstruct the recorded signal in the presence of disturbances caused by these foreign bodies.

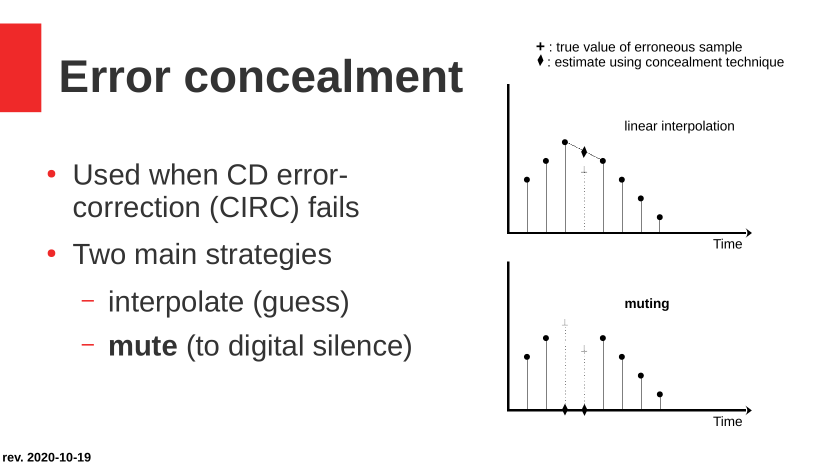

However, this error-correction system is not infallible. Additional processes—so-called “error concealment” techniques—are used to improve the apparent robustness of the recording medium to degradation and disruption. When an error is detected that cannot be corrected, the erroneous digital audio data is flagged to be later covered up by the player.28 Most error-concealment systems in CD players deploy two different techniques to mask the effect of bad data on playback. The first is interpolation: essentially a “best guess” for the missing audio sample data.29 But when a CD player encounters a long burst of known-bad data that is unsuitable for interpolation it falls back on a final, last-gasp technique to remedy the situation: simply muting altogether the audio output for the duration of the missing data.30

Temporarily muting the audio signal might seem like a drastic solution. But audio engineers at Philips involved in optical storage projects in the late 1970s made use of a finding from 1960s research that showed listeners could tolerate the occasional loss of musical signal for up to 10ms in duration without reporting significant annoyance.31 This result continued to motivate design decisions made in both the design of the compact disc format and its players: a clear example of what Jonathan Sterne called “perceptual technics” in action.32

Recovering this distinction between CD’s error correction and error concealment, and coupling it with Sterne’s insights, we see clearly how the listening subject is enrolled as a kind of human “interpolator”-of-last resort, but not before many other strategies for error control are algorithmically exhausted by each player.33 Muting, therefore, is not only an exceptional state of the CD player’s operation when paused or skipping between tracks—as Collins’s Broken Light initially suggests—but also is, in fact, a compensatory strategy that is available to CD players at any moment during playback. Though manufacturers estimated that such uncorrectable errors would be very infrequently encountered by consumers, preliminary research by intrepid audio reviewers suggested otherwise: in regular use, early CD players intervened regularly to conceal and ultimately mute sound much more often than manufacturers admitted.34 Thus, although it lies entirely beneath the limen of our perceptual capacities, these microscale silences were part and parcel of the technical-media setup of late-twentieth-century digital audio.

Conclusion

As Kromhout and others have pointed out, following Michel Chion, twentieth-century technologies of noise reduction have taught us how to attend to silence anew.35 The impressive signal-to-noise ratio that the audio CD format introduced—an unprecedented 96dB—seemed to do away with the need for noise reduction, at least as noise reduction had been conceptualised under the analog regime. Little wonder that the test and demonstration pressings that were created to showcase the format’s capabilities often contained tracks containing nothing but total silence, a jarring contrast to the sounds of jet engines and racquetball games also included on one such 1983 release.36 In other words, silence has always been part of the condition of high-fidelity audio reproduction.

But unlike the “digital zero” silent tracks on demo pressings and test discs, the silences introduced by error concealment are pervasive and they are imperceptible. Despite the promise of total control and a digital soundstage to rival the acoustics of Carnegie Hall, the algorithmic policies of sonic control that CD players implement made a subliminal sonic subterfuge—concealment and silence—an integral part of the late-twentieth-century consumer audio experience. I aim to have shown that one way that a hearing of Nicolas Collins’s Broken Light can light the way to this conclusion. His composition reveals how only the most technically adventurous users could expose, modify, and ultimately subvert at least some of these policies. But even the most committed hardware hacker would balk at the prospect of reprogramming the cryptic microchips inside the Sony Discman D-2 to prevent them from routinely excising errant sounds from our conscious perception. As difficult as it may be, this would be a radical act of media archaeology since it works to further dismantle CD’s mnemotechnical myth of “perfect sound forever”; this time around, from within.37

Funding acknowledgment

This research was supported by a Government of Ireland Postdoctoral Fellowship, awarded by the Irish Research Council in 2019 to Eamonn Bell for the project “Opening the ‘Red Book’: The digital Audio CD format from the viewpoint between musicology and media studies.” Project no. GOIPD/2019/239.

Works cited

Akrich, Madeline. “The de-Scription of Technical Objects.” In Shaping Technology/Building Society, edited by W. Bijker and John Law, 205–24. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992.

Anderson, Tim J. “Training the Listener: Stereo Demonstration Discs in an Emerging Consumer Market.” In Living Stereo: Histories and Cultures of Multichannel Sound, edited by Paul Théberge, Kyle Devine, and Tom Everrett, 107–24. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Benson-Allott, Caetlin Anne. Remote Control. Object Lessons. New York, NY, 2015.

Bohlman, Andrea F., and Peter McMurray. “Tape: Or, Rewinding the Phonographic Regime.” Twentieth-Century Music 14, no. 1 (February 2017): 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478572217000032.

Cardozo, B. L., and G. Domburg. “An Estimation of Annoyance Caused by Dropouts in Magnetically Recorded Music.” Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 16, no. 4 (October 1, 1968): 426–29. http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=1620.

Chion, Michel. “Silence in the Loudspeakers.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 40 (April 1999): 106–10.

Daniel, Ryan. “Digital Disruption in the Music Industry: The Case of the Compact Disc.” Creative Industries Journal 12, no. 2 (May 4, 2019): 159–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2019.1570775.

Downes, Kieran. “"Perfect Sound Forever": Innovation, Aesthetics, and the Re-Making of Compact Disc Playback.” Technology and Culture 51, no. 2 (2010): 305–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40647101.

Ernst, Wolfgang. Digital Memory and the Archive. Edited by Jussi Parikka. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

———. Sonic Time Machines: Explicit Sound, Sirenic Voices, and Implicit Sonicity. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press B. V., 2016.

Gane, Nicholas. “Radical Post-Humanism: Friedrich Kittler and the Primacy of Technology.” Theory, Culture & Society 22, no. 3 (June 2005): 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276405053718.

Geoghegan, Bernard Dionysius. “After Kittler: On the Cultural Techniques of Recent German Media Theory.” Theory, Culture & Society 30, no. 6 (November 1, 2013): 66–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413488962.

Hainge, Greg. Noise Matters: Towards an Ontology of Noise. Sound Studies. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Acad, 2013.

Hirsch, Julian D. “Stereo Review Tests 11 Digital Compact Disc Players.” Stereo Review, July 1983.

Kelly, Caleb. Cracked Media: The Sound of Malfunction. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2009.

Kittler, Friedrich. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Writing Science. 1986. Reprint, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Kittler, Friedrich A. “Protected Mode.” In Literature, Media, Information Systems: Essays, edited by John Johnston. Critical Voices in Art, Theory and Culture. London; New York: Routledge, 2012.

Kromhout, Melle. “An Exceptional Purity of Sound: Noise Reduction Technology and the Inevitable Noise of Sound Recording.” Journal of Sonic Studies 7 (June 26, 2014). https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/84544/84545/2753/242.

Miyazaki, Shintaro. “Take Back the Algorithms! A Media Theory of Commonistic Affordance.” Media Theory 3, no. 1 (August 23, 2019): 269–86. http://journalcontent.mediatheoryjournal.org/index.php/mt/article/view/89.

Mowitt, J. “The Sound of Music in the Era of Its Electronic Reproducibility.” In Music and Society: The Politics of Composition, Performance, and Reception, edited by Richard D. Leppert and Susan McClary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Nakai, You. “Hear After: Matters of Life and Death in David Tudor’s Electronic Music.” Communication + 1 3, no. 1 (September 2014). https://doi.org/10.7275/R5GT5K3F.

Peek, Hans B. “The Emergence of the Compact Disc.” IEEE Communications Magazine 48, no. 1 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2010.5394021.

Peek, J. B. H., ed. Origins and Successors of the Compact Disc: Contributions of Philips to Optical Storage. Philips Research, v. 11. Dordrecht: Springer, 2009.

Perlman, Marc. “Consuming Audio: An Introduction to Tweak Theory.” Tijdschrift Voor Mediageschiedenis 6, no. 2 (2003): 117–28. https://doi.org/10.18146/tmg.235.

Plasketes, George. “Romancing the Record: The Vinyl de-Evolution and Subcultural Evolution.” The Journal of Popular Culture 26, no. 1 (1992): 109–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.1992.00109.x.

Pohlmann, Ken C. The Compact Disc Handbook. 2nd ed. The Computer Music and Digital Audio Series, v. 5. Madison, WI: A-R Editions, 1992.

Poss, Robert. “The Unconventional Has Been Conventional for so Long [Interview with Nicolas Collins].” Tape Op. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://www.nicolascollins.com/texts/collinsposstapeop.pdf.

Ranada, David. “Digital Debut: First Impressions of the Compact Disc System.” Stereo Review, December 1982.

Shenton, David, Erik DeBenedictis, and Bart Locanthi. “Error Correction for PCM Digital Audio Systems.” Presented at AES 1981 (?) but not included in proceedings. 1981. Pasadena, CA: Pioneer North America. Accessed October 14, 2020. http://debenedictis.org/erik/Reports-1981/EC-PCM.pdf.

Siegert, Bernhard. “Mineral Sound or Missing Fundamental: Cultural History as Signal Analysis.” Osiris 28, no. 1 (January 2013): 105–18. https://doi.org/10.1086/671365.

Sterne, Jonathan. MP3: The Meaning of a Format. Sign, Storage, Transmission. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

Teboul, Ezra. “Electronic Music Hardware and Open Design Methodologies for Post-Optimal Objects.” In Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities, edited by Jentery Sayers. University of Minnesota Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt1pwt6wq.

Teboul, Ezra J. “A Method for the Analysis of Handmade Electronic Music as the Basis of New Works.” PhD diss., Rennslaer Polytechnic Institute, 2020. https://n2t.net/ark:/13960/t6745pb14.

Thompson, Marie. Beyond Unwanted Sound: Noise, Affect and Aesthetic Moralism. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Winthrop-Young, Geoffrey. “The Kittler Effect.” New German Critique 44, no. 3 (132) (November 2017): 205–24. https://doi.org/10.1215/0094033X-4162322.

Winthrop-Young, Geoffrey, and Nicholas Gane. “Friedrich Kittler: An Introduction.” Theory, Culture & Society, June 30, 2016. 10.1177/0263276406069874.

Caleb Kelly, Cracked Media: The Sound of Malfunction (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2009)↩︎

Greg Hainge, Noise Matters: Towards an Ontology of Noise, Sound Studies (New York, NY: Bloomsbury Acad, 2013), 133–135.↩︎

Like Melle Kromhout, I’m wary of the difficulties that attend attempts to pin down “noise”: informal–sociological and formal–mathematical definitions of noise are not always compatible with each other, and accounts of noise that loose touch with such fine and essentially technical distinctions are of limited use. Melle Kromhout, “An Exceptional Purity of Sound: Noise Reduction Technology and the Inevitable Noise of Sound Recording,” Journal of Sonic Studies 7 (June 26, 2014), https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/84544/84545/2753/242.↩︎

For the theoretical point made explicit see Marie Thompson, Beyond Unwanted Sound: Noise, Affect and Aesthetic Moralism (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017), 54. For Thompson’s discussion of Broken Light, see Thompson, 162–164.↩︎

This is in part a response to Hainge’s explicit call for greater technical precision in the description of mediated noise music.↩︎

You Nakai, “Hear After: Matters of Life and Death in David Tudor’s Electronic Music,” Communication + 1 3, no. 1 (September 2014), https://doi.org/10.7275/R5GT5K3F; Ezra Teboul, “Electronic Music Hardware and Open Design Methodologies for Post-Optimal Objects,” in Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities, ed. Jentery Sayers (University of Minnesota Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt1pwt6wq; Ezra J. Teboul, “A Method for the Analysis of Handmade Electronic Music as the Basis of New Works” (PhD diss., Rennslaer Polytechnic Institute, 2020), https://n2t.net/ark:/13960/t6745pb14.↩︎

On the translation of Kittler into North American academe, see Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, “The Kittler Effect,” New German Critique 44, no. 3 (132) (November 2017): 205–24, https://doi.org/10.1215/0094033X-4162322.↩︎

Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, Writing Science (1986; repr., Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999). Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Nicholas Gane, “Friedrich Kittler: An Introduction,” Theory, Culture & Society, June 30, 2016, 10.1177/0263276406069874. See also, Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan, “After Kittler: On the Cultural Techniques of Recent German Media Theory,” Theory, Culture & Society 30, no. 6 (November 1, 2013): 66–82, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413488962.↩︎

Handmade Experimental Music. Unencumbered by lofty theorizing, a subversive and anti-authoritarian streak runs through Collins’s work, especially in a rich seam of compositions that the potential for creative expression that is latent in consumer electronics.↩︎

I Musici, Christmas Concertos: Corelli, Manfredini, Torelli, Locatelli. Recorded 1984. Philips 412 739-2, 1990. CD.↩︎

Robert Poss, “The Unconventional Has Been Conventional for so Long [Interview with Nicolas Collins],” Tape Op, accessed October 14, 2020, https://www.nicolascollins.com/texts/collinsposstapeop.pdf, supplement to printed version of interview available at Collin’s personal website.↩︎

Nicolas Collins, Broken Light 1991 rev. 1992, 1. Available for perusal at the composer’s website. https://www.nicolascollins.com/texts/brokenlightscore.pdf.↩︎

Wolfgang Ernst, Sonic Time Machines: Explicit Sound, Sirenic Voices, and Implicit Sonicity (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press B. V., 2016).↩︎

Ernst is optimistic about the usefulness of computational devices—especially spectrographs and the related Fourier transformation—to the doing of media archaeology. “By applying technomathematical analysis, media archaeology access the subsemantic strata of culture.” Wolfgang Ernst, Digital Memory and the Archive, ed. Jussi Parikka (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 59. See also, Bernhard Siegert, “Mineral Sound or Missing Fundamental: Cultural History as Signal Analysis,” Osiris 28, no. 1 (January 2013): 105–18, https://doi.org/10.1086/671365.↩︎

George Plasketes, “Romancing the Record: The Vinyl de-Evolution and Subcultural Evolution,” The Journal of Popular Culture 26, no. 1 (1992): 109–22, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.1992.00109.x, 112.↩︎

Mnookin quoted in Ryan Daniel, “Digital Disruption in the Music Industry: The Case of the Compact Disc,” Creative Industries Journal 12, no. 2 (May 4, 2019): 159–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2019.1570775, 161.↩︎

Of course, while some of the new playback controls enabled by CD technology were novel, their development was presaged by earlier media. Push-button interfaces brought a “command and control” paradigm into the studio and the home as early as the 1960s on, as Andrea Bohlman and Peter McMurray have shown in relation to tape players. Andrea F. Bohlman and Peter McMurray, “Tape: Or, Rewinding the Phonographic Regime,” Twentieth-Century Music 14, no. 1 (February 2017): 3–24, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478572217000032.↩︎

Caetlin Anne Benson-Allott, Remote Control, Object Lessons (New York, NY, 2015), 80.↩︎

This ad ran, for example, in HiFi and Stereo Review. September 1983, 51.↩︎

Marc Perlman, “Consuming Audio: An Introduction to Tweak Theory,” Tijdschrift Voor Mediageschiedenis 6, no. 2 (2003): 117–28, https://doi.org/10.18146/tmg.235. See also, Kieran Downes, “"Perfect Sound Forever": Innovation, Aesthetics, and the Re-Making of Compact Disc Playback,” Technology and Culture 51, no. 2 (2010): 305–31, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40647101, 323. These products, which did little other than cater to the customer’s desire to do something—anything!—to tune and refine their now inscrutable hi-fi system included rubber rims intended to stabilize CDs as they rotated at speed, green-ink markers to improve the reflectivity of the disc surface, and even the cryogenic treatment of discs using liquid nitrogen.↩︎

In 1979, it sported a full view of the spinning disc from above. The first commercially produced Philips player, on the other hand, the CD-100, gave a partial view on the disc; subsequent models revealed even less of the disc in motion and relinquishing the design motif entirely with the CD-104, which adopted their implementation of the tray-loading mechanism pioneered by Sony.↩︎

This notion is not dissimilar to what Akrich calls the “script” of a technical object. Madeline Akrich, “The de-Scription of Technical Objects,” in Shaping Technology/Building Society, ed. W. Bijker and John Law (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992), 205–24.↩︎

Or what Akrich calls “de-scription”.↩︎

Nicholas Gane, “Radical Post-Humanism: Friedrich Kittler and the Primacy of Technology,” Theory, Culture & Society 22, no. 3 (June 2005): 25–41, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276405053718, 34–35.↩︎

Friedrich A. Kittler, “Protected Mode,” in Literature, Media, Information Systems: Essays, ed. John Johnston, Critical Voices in Art, Theory and Culture (London; New York: Routledge, 2012). See also, Shintaro Miyazaki, “Take Back the Algorithms! A Media Theory of Commonistic Affordance,” Media Theory 3, no. 1 (August 23, 2019): 269–86, http://journalcontent.mediatheoryjournal.org/index.php/mt/article/view/89.↩︎

However, it has, based on recent conversations I have had, concern for audio preservation engineers for some time now.↩︎

For a reasonably accessible and technically accurate description of these techniques, see Ken C. Pohlmann, The Compact Disc Handbook, 2nd ed., The Computer Music and Digital Audio Series, v. 5 (Madison, WI: A-R Editions, 1992).↩︎

J. B. H. Peek, ed., Origins and Successors of the Compact Disc: Contributions of Philips to Optical Storage, Philips Research, v. 11 (Dordrecht: Springer, 2009), 65–66.↩︎

The distinction between error detection, correction, and concealment is critical here.↩︎

This muting is applied gradually, to reduce “clicking” transients in the DAC that would be due to the discontinuities introduced by immediately zeroing out the samples.↩︎

Hans B. Peek, “The Emergence of the Compact Disc,” IEEE Communications Magazine 48, no. 1 (2010), https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2010.5394021, 13. For the original study, see B. L. Cardozo and G. Domburg, “An Estimation of Annoyance Caused by Dropouts in Magnetically Recorded Music,” Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 16, no. 4 (October 1, 1968): 426–29, http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=1620. Analogous research carried out by Pioneer found that listeners would tolerate as many as 1000 concealments per minute if the recorded program was a musical one. Less complex sounds, such as pure sine tones, reveal the negative effects of concealment on high-definition reproduction more clearly. David Shenton, Erik DeBenedictis, and Bart Locanthi, “Error Correction for PCM Digital Audio Systems,” Presented at AES 1981 (?) but not included in proceedings. (1981; Pasadena, CA: Pioneer North America), accessed October 14, 2020, http://debenedictis.org/erik/Reports-1981/EC-PCM.pdf.↩︎

Jonathan Sterne, MP3: The Meaning of a Format, Sign, Storage, Transmission (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012). Albeit a not especially sophisticated one when contrasted with the masking techniques used in the MP3 format that Sterne describes. Nevertheless, Sterne’s notion apropos: the intention behind the error-correcting schemes used in digital optical disc media was not (primarily) to make the format resistant to scratches etc., but to overcome certain manufacturing limitations which, in the early days of disc manufacture, led to the inevitable introduction of defects on disc media. The adoption of digital representations of audio raised the stakes for these defects, given the “cliff-edge” nature of (binary) digital representations: a sign on the medium represents either a 0 or a 1. I discuss this elsewhere (unpublished as of October 2020).↩︎

Compare with Hainge, Noise Matters, 135.↩︎

David Ranada, “Digital Debut: First Impressions of the Compact Disc System,” Stereo Review, December 1982, 70.↩︎

Kromhout, “An Exceptional Purity of Sound.”. Michel Chion, “Silence in the Loudspeakers,” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 40 (April 1999): 106–10.↩︎

For instance, the Philips test disc Test Sample 3 (TS3) and the Sony test disc YEDS 2 both contained entirely silent tracks. Julian D. Hirsch, “Stereo Review Tests 11 Digital Compact Disc Players,” Stereo Review, July 1983, 45. The Digital Domain (Elektra, 1983). For a discussion of demo discs in the multichannel audio context, see Tim J. Anderson, “Training the Listener: Stereo Demonstration Discs in an Emerging Consumer Market,” in Living Stereo: Histories and Cultures of Multichannel Sound, ed. Paul Théberge, Kyle Devine, and Tom Everrett (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), 107–24.↩︎

Downes, “"Perfect Sound Forever".”, 317–318. See also J. Mowitt, “The Sound of Music in the Era of Its Electronic Reproducibility,” in Music and Society: The Politics of Composition, Performance, and Reception, ed. Richard D. Leppert and Susan McClary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).↩︎